Indian Removal

Lesson Plan

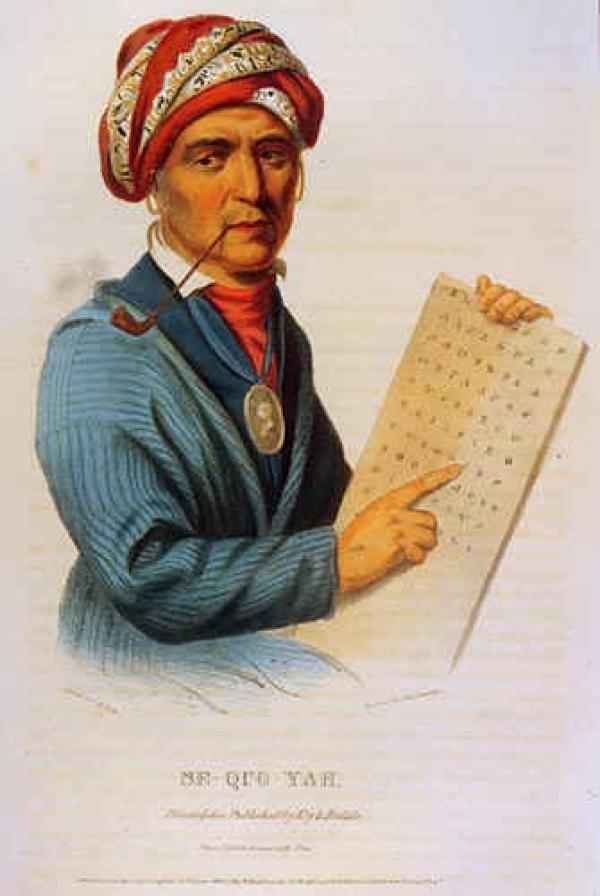

(above) Sequoya, creator of the Cherokee alphabet

Introduction

By the terms of the Indian Intercourse Act of 1790, Indian land could be acquired by the United States only when ceded by treaty. However, peaceful intentions and hopes for the assimilation of Native Americans yielded to the pressure of westward expansion, which inevitably shaped Indian policy. This lesson looks at the process whereby a policy of assimilation gave way to one of overt removal under President Jackson.

Objectives

1. To compare the policies toward Native Americans pursued by the presidential administrations through the Jacksonian era.

2. To evaluate the impact of assimilation, removal, and resettlement on Native Americans.

Part 1

Students should become familiar with presidential Indian policy, beginning with Thomas Jefferson’s policy of acculturation and assimilation. In his First Annual Message he endorsed “continued efforts to introduce among them the implements and the practice of husbandry, and of the household arts.” He reiterated this position in his State of the Nation Addresses of 1807 and 1808. Students should carefully note Jefferson’s expectation that assimilation would put Indian land into white hands. Two sites give full texts of Indian treaties: the first, between Indian nations and the United States; the second, restricted to treaties with the Chickasaw and those nations significant to the Chickasaw.

For those nations that did not wish to assimilate, Jefferson offered them removal to territory west of the Mississippi. Within two decades, at the insistence of the Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi legislatures and the urging of Andrew Jackson, removal became the nation’s official policy. This policy had widespread public support among Americans. Students should read the full text of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The debate in the Senate over removal contains the forceful speeches of Maine Senator Peleg Sprague and Georgia Senator John Forsyth, against and for removal respectively. President Jackson’s First, Second, and Seventh Annual Messages deal with Indian removal.

The southern states’ efforts to invalidate federal treaties and open Indian land to whites mounted a sectional challenge to federal authority; Jackson responded to these state challenges by pressuring tribes into signing removal treaties. The Cherokee resisted these efforts and brought suit in court. If teachers want to provide a broader context for this challenge, they can visit--or refer students to-- the Wisconsin Judicare’s Indian Law Office’s collection of Federal Indian laws. This collection includes the full text of Supreme Court decisions in Cherokee Nation v. State of Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. State of Georgia (1832). When Jackson refused to enforce the Supreme Court decisions that favored the Cherokee, a tribal faction pushed through the Treaty of New Echota, which acceded to removal. The part of Georgia occupied by the Cherokee in 1830 may be compared to the antebellum expansion of cotton production. Removal forts were built in Georgia to house the Cherokee before their journey west. An 1836 map shows each tribe’s assigned lands in Indian Territory. Another map shows the routes taken by the southeastern tribes to reach the new lands.

Having studied the solidification of removal policy under Jackson, students may be given an 1833 cartoon to explicate. "The Grand National Caravan Moving East" satirizes Jackson's removal policy. Because the caged Indian in the caravan represents the Sauk leader Black Hawk, ask the students to explain the ways in which dispossession of tribes in the Old Northwest compared with that of the five Southeastern tribes. The students should also account for the incongruous “Rights of Man” banner and liberty cap atop the cage.

Part 2

Introduce students to assimilation through the Cherokee alphabet devised by Sequoyah; the Cherokee-language newspaper; and the 1827 Cherokee Constitution. Ask the students to compare and contrast the U.S. and Cherokee Constitutions.

Elias Boudinot, editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, made “An Address to the Whites" in Philadelphia in 1826. Two years later, he expressed concern about the mounting voices that discounted assimilation:

It appears that the advocates of this new system of civilizing the Indians are very strenuous in maintaining the novel opinion that it is impossible to enlighten the Indians, surrounded as they are by the white population, and that they assuredly will become extinct, unless they are removed. It is a fact which we would not deny that many tribes have perished away in consequence of white population, but we are yet to be convinced that this will always be the case, in spite of every measure taken to civilize them. We contend that suitable measures to a sufficient extent have never been employed. And how dare these men make an assertion without sufficient evidence? What proof have they that the system which they are now recommending will succeed? Where have we an example in the whole history of man, of a Nation or tribe, removing in a body, from a land of civil and religious means, to a perfect wilderness, in order to be civilized? We are fearful these men are building castles in the air, whose fall will crush those poor Indians who may be so blinded as to make the experiment. We are sorry to see that some of the advocates of this system speak so disrespectfully, if not contemptuously, of the present measures of improvement, now in successful operation among most of the Indians in the US -- the only measures too, which have been crowned with success and bid fair to meliorate the condition of the Aborigines. -- Elias Boudinot (Cherokee Newspaper editor) on Removal and "civilization" efforts, 1828

Reaction to removal was considerable and vocal. The Chickasaw Historical Research page contains letters written by the Chickasaw to U.S. officials. John Ross of the Cherokee presented a memorial to Congress protesting removal in 1836. Students may refer to this site for an account of conditions on the Trail of Tears, which received this treatment by Robert Lindneux in 1928. Read addresses delivered by General Winfield Scott to the troop escorts and to the Cherokee.

The topic of Indian Removal lends itself to especially well an in-class debate. Divide the students into small groups that will each represent one of the contemporary voices raised on this issue: assimilationists, such as Thomas Jefferson; staunch advocates of federal removal, such as Andrew Jackson; white citizens of southern states hungry for Indian lands; the Supreme Court, represented by Chief Justice John Marshall; Cherokee such as John Ross who championed assimilation and refusal to relocate; the signers of the New Echota treaty, such as Elias Boudinot, who acquiesced to federal pressures; Christian missionaries who supported Cherokee self-determination; and the tribes of the Old Northwest, who rose in resistance. Each group should develop a set of debate points that capture the content and flavor of the contemporary debate. It is essential that each group conduct itself as much as possible as contemporaries would. A spokesperson may be assigned in each group; this student might be one who needs to participate more in class. You might also appoint a jury to assess each group’s arguments and decide whether pro-removal or anti-removal voices carried the day.