Stereotypes in Cartoons

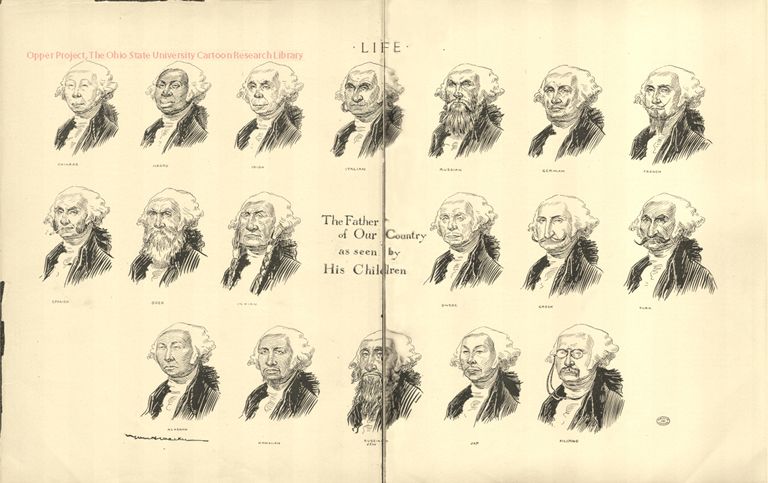

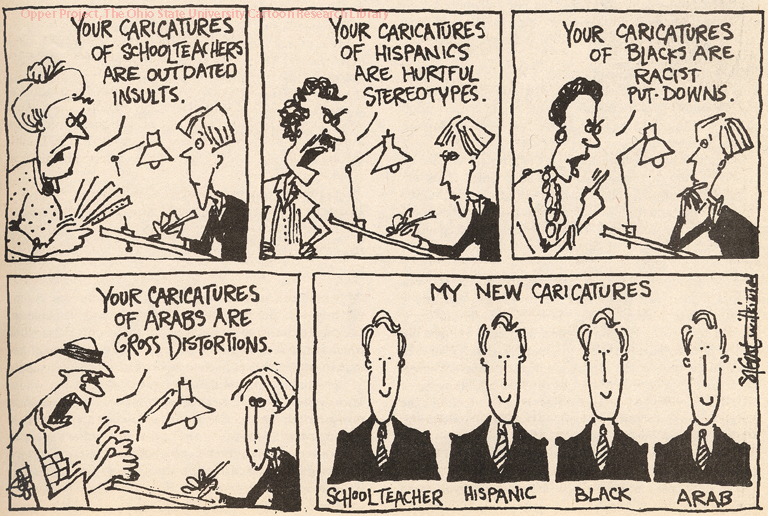

Stereotypes are a type of symbol used by cartoonists. Just as a light bulb above an American comic strip character's head is understood to mean an inspiration, stereotypes symbolize groups of people or complex ideas that are quickly and easily interpreted by readers. Cartoonists use stereotypes as part of a visual shorthand to communicate complicated ideas quickly and effectively.

The term stereotype originally described a printing method in which a metal printing plate was formed from a papier-mâché or plaster mould of the movable type so that the plate could be used repeatedly without alteration and the movable type recycled to be set again for something else. The American Heritage Dictionary (4th ed. 2000) defines stereotype as "A conventional, formulaic, and oversimplified conception, opinion, or image."

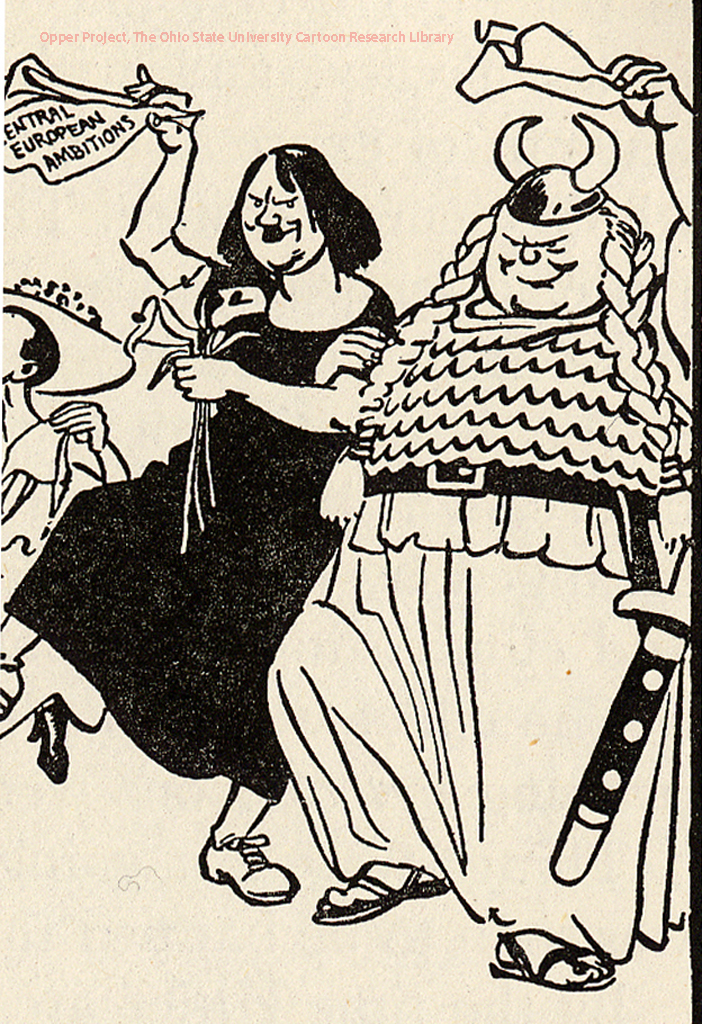

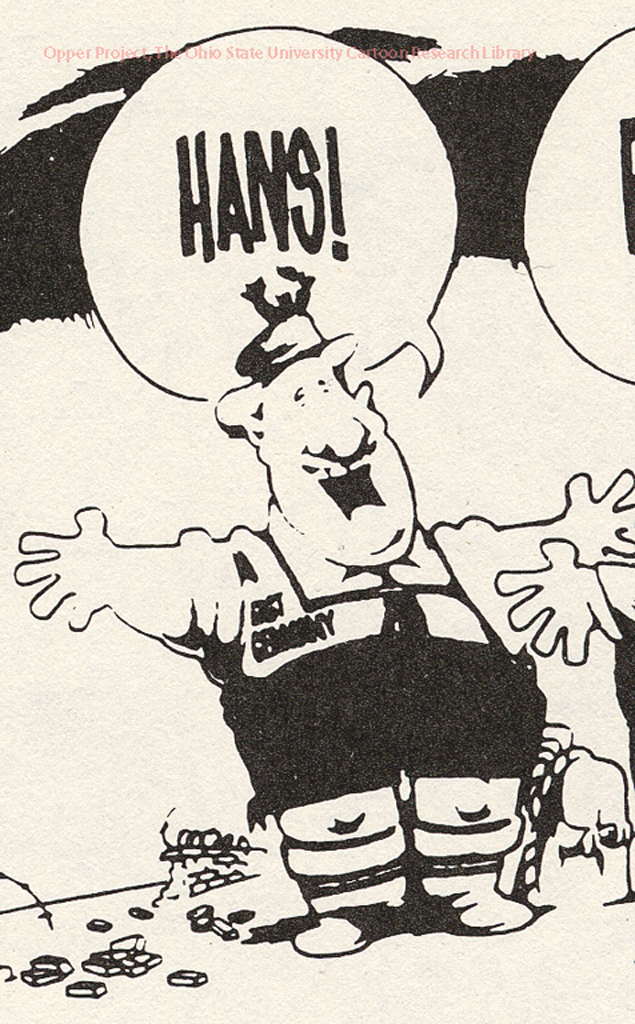

Stereotyping is part of the history of American humor. Stereotypes may represent ideas, nations, or groups of people. In addition to racial and ethnic characteristics, indicators of economic status such as clothing may be used in stereotypes. Without easily interpreted stereotypes, cartoons would require paragraphs of text and much more detailed drawings to transmit information. The list of peoples exploited by cartoonists includes more than ethnic and religious groups. Women, rural Americans ("the country bumpkin"), the wealthy, hoboes (the 19th and early 20th century equivalent of the homeless), intellectuals, professors, the elderly, scientists, poets, members of Congress -- the list goes on and on.

Cartoon art depicting racial and ethnic characteristics may be based on assumed physical characteristics or alleged religious practices that have a kernel of legitimacy in real physical traits or actual ritual. This trace of reality makes negative stereotypes particularly effective and difficult to combat, since they appear to be accurate in the opinion of those who hold them.

Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, ethnicity was the topic of many magazine cartoons. Most of these cartoons are not understood by today's readers as humorous. Their crude wit provides a revealing glimpse of the history of race relations and religious tolerance in the United States.

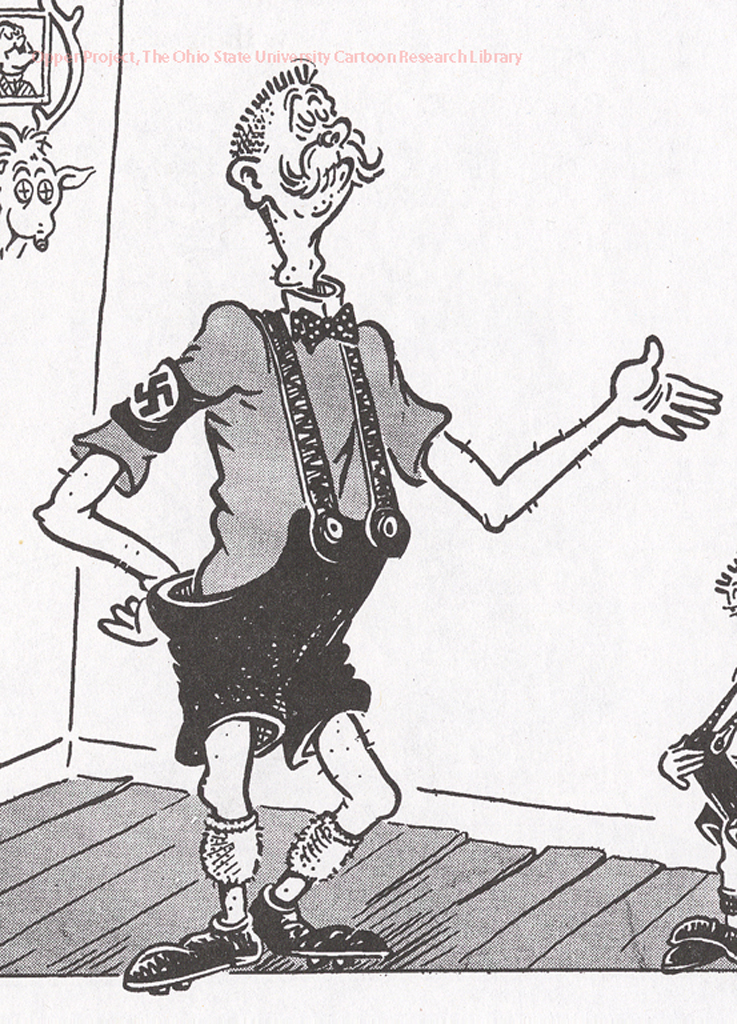

American cartoonists used racial and ethnic stereotypes as soon as large numbers of non-Anglo-Saxon Protestants began arriving in America in the 1840s. First to be lampooned were the Irish; then, as the abolitionist movement progressed, African Americans; next came the Jews, Germans, and Chinese; and finally by the turn of the century, the Italians.

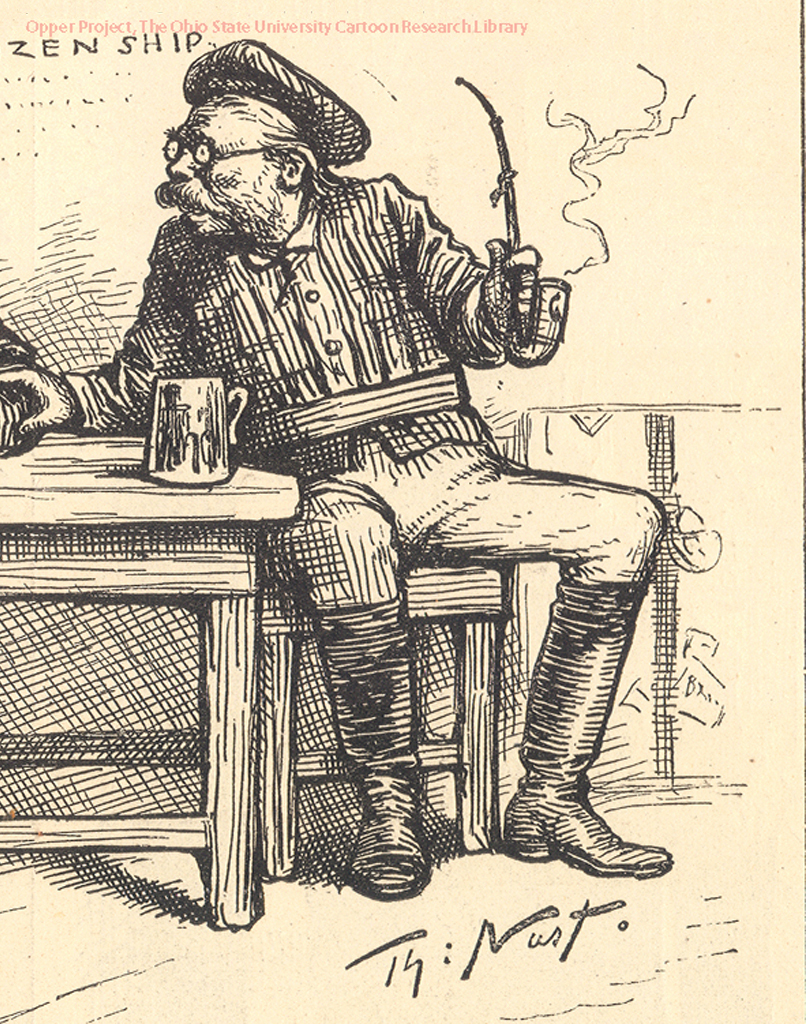

East Coast cartoonists, depending on their politics, tended to single out one group or another. Thomas Nast and Joseph Keppler despised the Irish (particularly Irish Catholics), H.L. Stephens hated African Americans. James A. Wales and the cartoonists of the first Life magazine were anti-Semites. Because there were so few Chinese on the East Coast, eastern cartoonists either ignored them or made fun of their colleagues on the West Coast who were so obsessed with their presence among them.

The history of racial and ethnic stereotypes is not a proud history, but it is a part of history. Editorial cartoons document the time in which they were created. Some of the images in historical editorial cartoons are ugly, but editorial cartoons from the past cannot be judged by current standards. The challenge is to try to understand the time in which the cartoons were produced.

Cartoons

Aw, Schucks

Hobo

The Father of Our Country as Seen by His Children

Which Color is to be Tabooed Next

Food? We Germans don't eat food! We Germans eat countries!

The Girls He Left Behind Him

Hans! Franz!

My New Caricatures